Our Brothers in the Camps

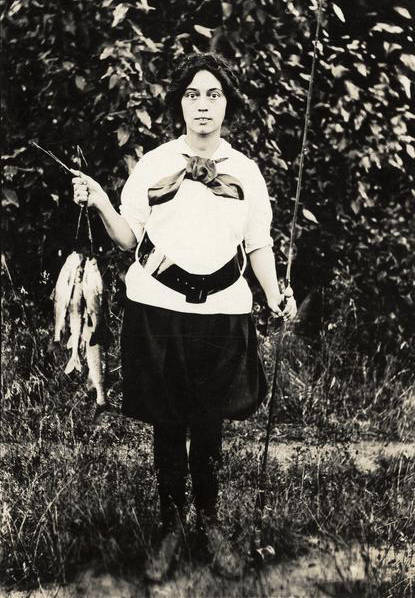

Opal Whiteley, age 17 circa late 1916

English Composition Assignment, Freshman term

University of Oregon

520 words

NOTE: THIS IS AN ASSIGNMENT OF OPAL’S AT THE UO. I HAVE INCLUDED ITS SCANS AND A COMMENTARY

Commentary by Steve Williamson

Opal Whiteley is often seen as a princess of the environmental. Indeed most of her fans enjoy her writings about nature and the forests best of all. Yet, Opal was a child of a logging and gold mining family. She grew up in these lumber camps, moving often. While Opal later denied her family, she always writes positively about the men and women who work in the timber industry. In her childhood diary, it is a logger, the man who wears grey neckties who gives her paper & pens – as does Sadie McKibben, whose family owns the mill by the far woods.

Opal Whiteley’s 1919 book, the Fairyland Around Us is filled with tributes to the forests and the people who work in them. This short story, composed for a writing assignment in her freshman year of 1916, implores her readers to understand and appreciate the hard work of lumberjacks.

In some ways this story, Our Brothers in the Camps, is more like a morality tale than a short story. It is much like the sort of lectures and sermons Opal both heard and gave when she was growing up. It starts as a short story, but soon turns into a ringing defense of working men and women. It is closer to a sermon than a short story.

Opal even uses the term “comrade”, a popular Marxist term at the time of the Russian Revolution. The rich stranger from town learns a lesson in humanity by his visit to the lumber camp. But, there is also a favorable portrait of the local woods “Boss”. Opal is more interested in the urban-rural divide than in management-labor disputes. In fact, perhaps she is most interested in the common humanity and value of each person. It’s clear she judges people not on their wealth, but on their kindness and work.

What sort of young person would write a story like Our Brothers in the Camps? It impresses me as a person who is feeling isolated from her friends and home. It also shows how much she craves acceptance – before she had always been a “big fish in a small pond” – now she was one student among thousands. Her peers at the university still saw her as an oddity from a place people made fun of. This story may be her response to perceived prejudice from city kids towards a girl from the country.

Opal’s passion for the lumberjacks comes through the typed text but look if you will, carefully over her handwritten original. Notice how her handwriting consistently moves upward and at times even sloping up and down in once sentence making her words look like they are smiling. This is not just a collegiate essay – it her own testament.

Opal uses a several terms that some readers may not be family with. For example, a “donkey engine” was a powerful motor that pulled logs to the mill or up a steep slope. She also uses the word “chute”, which is how logs were sent to the mill. There is a picture of a donkey engine on this website.

Most lumber camps were small, having anywhere from five to fifty families. Everyone knew each other. A logging camp was a temporary settlement of a lumber mill and the lumber shanties for the workers. Once the nearby trees were cut, the entire operations, the mill and the small houses would be moved by railroad to a new place to cut trees.

In some ways this paper may sound like many that freshman or sophomore students have written. Young people have a strong sense of justice and what is “right” in their eyes. Indeed, there were many books and publications in her day about the dignity of labor. Most students are simply repeating what they have read – but not Opal. She has actually lived the life she writes about. She has seen many men die in the ten years she has lived in lumber camps. Few freshmen had seen so much death as Opal.

Opal’s paper describes the fear each person in the camps feels when they hear the four blasts of the mill’s whistle signaling a severe accident. Opal has personally known the terror that it could be her parent or friend who has been injured. She knew what it was like to feel both relief and guilt upon learning that it was a member of someone else’s family who has been killed. Today, we might call it “survivor”s guilt”.

Note how Opal proudly uses the word “Lumberjack” in this story. In her day, this word was considered a derogatory term, something like how “redneck” might be used today. Lumberjack was the term used before chainsaws were invented. After that the men were called loggers or lumbermen. Lumberjacks had the highest mortality rate of any industrial worker except deep mining. Death was a daily threat in logging camps. Opal turns this derogatory term into a positive. She asks her readers to consider the essential humanity of those who work hard for us.

Opal at the University of Oregon, Sept 1916 – Feb 1918

Opal Whiteley entered the UO with more fanfare than a modern football star , no one could have lived up to the academic expectations of her. She took on too much course work, enrolling both at the UO and at a Bible college while she still had to take a high school class in Springfield. Opal was still president of Jr. Christian Endeavor, which required much travel and communications. Opal also started a nature lovers club and even played the sport of Lacrosse.

She had long dreamed of going to college and literally jumped into every academic course she could enroll in. She had only been to Eugene twice in her life before enrolling in the university. It was a whole new world of libraries and scholars – but also of urban snobbery towards rural people. One of her professors was later to tell Inez Fortz “Opal was in the university, but never of the university”.

Her Mother was dying of cancer and sister moved to Eugene for Opal to take care of her. Opal had to take extra job and sell ferns & plants and wood to make ends meet. Opal’s mother a very painful, delusional death of cancer in May 1917 – just six months after this story was written. Opal spent much of her time taking care of her mother and younger sisters, even taking a second job. Opal’s mother had wanted Opal to quit school and take care of them. This could have been a main reason for her dropping out and leaving when she did.

Opal left Oregon in early 1918 partly because her family was pressuring her to take care of her four younger siblings after the death of their mother. Like many young women who have been faced with this choice, Opal chose to lead her own life. This caused the first major split with her family long before her diary was published in 1920.

She was not well accepted by her peers. She was considered “odd” – doing things like singing to earthworms and running across campus to catch butterflies. Opal was still deeply religious at a time when other young people were pulling away from the ties of church. But, hers was a more liberal, tolerant form of Christianity championed by Christian Endeavor and the U of O’s own Prof Thomas Condon, a well known minister who was also a highly respected scientist and writer on evolution and natural history.

Being from a rural area, Opal was largely taught by teachers who were themselves often self taught. It wasn’t until 1905 that Oregon began requiring teachers to have any education beyond their own reading. However, many of these rural women became excellent teachers. Opal had several teachers who are known to have inspired her. Teachers like Norma Williamson, Lily Black and Francis Dugan may have not known the correct way to pronounce a Greek name, but they well knew the facts behind it.

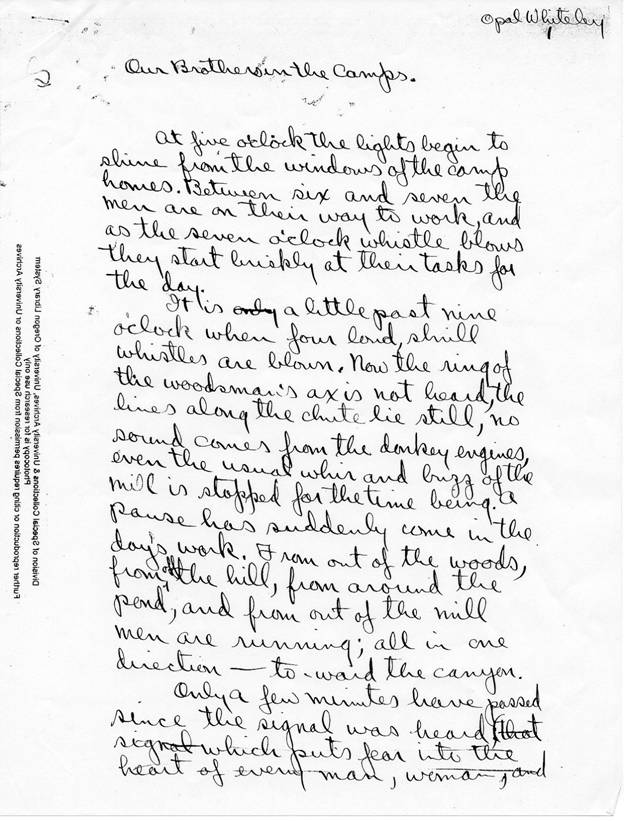

Our Brothers in the Camps

By Opal Whiteley

“At five o’clock the lights begin to shine from the windows of the camp homes. Between six and seven the men are on their way to work, and as the seven o’clock whistle blows they start briskly at the tasks for the day.

It is a little past nine o’clock when four loud shrill whistles are blown. Now the ring of the woodsman’s ax is not heard, the lines along the chute lie still, no sound comes from the donkey engines, even the usual whir and buzz of the mill is stopped for the time being. A pause has suddenly come in the day’s work. From out of the woods, from off the hill, from around the pond, and from out of the mill men are running; all in one direction – toward the canyon.

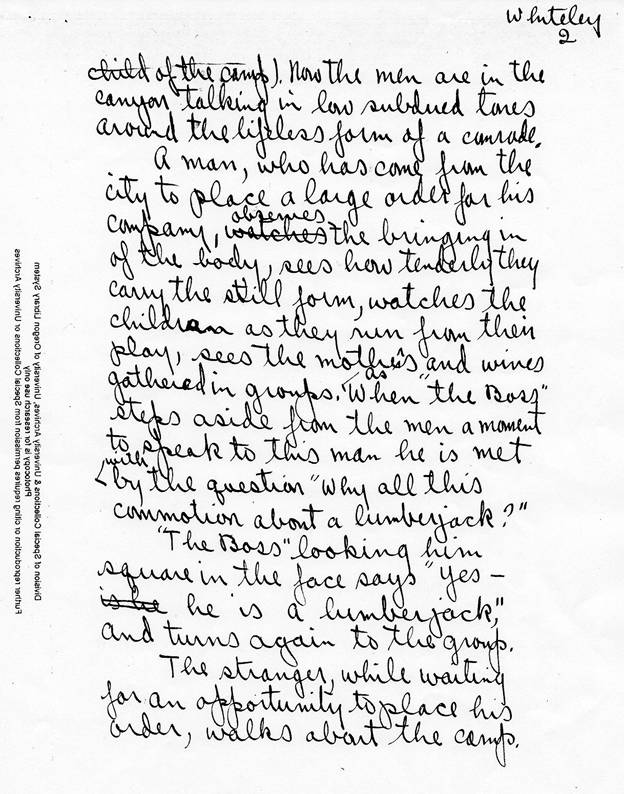

Only a few minutes have passed since the signal was heard (that signal which puts fear into the heart of every man, woman, and child of the camp). Now the men are in the canyon talking in low subdued tones around the lifeless form of a comrade.

A man, who has come from the city to place a large order for his company, observes the bringing in of the body, sees how tenderly they carry the still form, watches the children as they run from their play, sees the mothers and wives gathered in groups. As when the Boss steps aside from the men a moment to speak to this man he is met with by the question. Why all this commotion about a lumberjack?

The Boss looking him square in the face says “Yes, he is a lumberjack”, and turns again to the group.

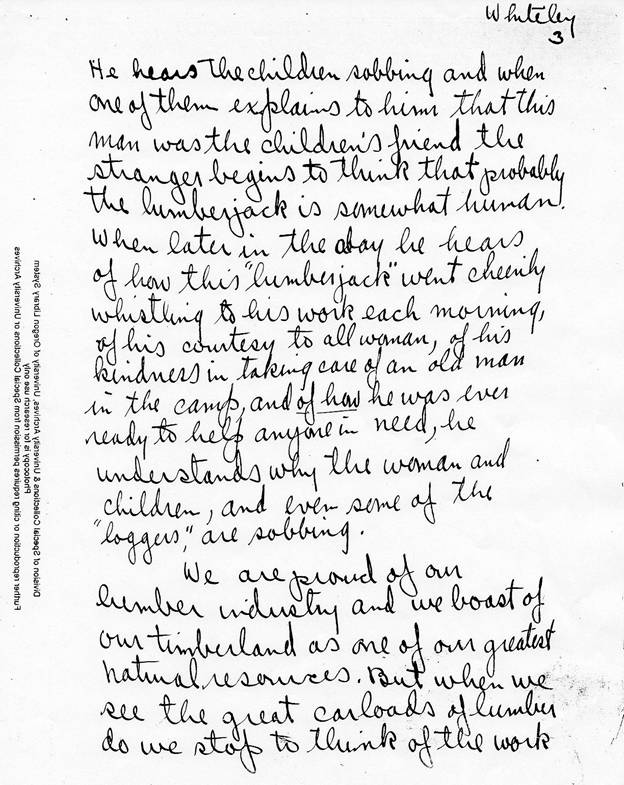

The stranger, while waiting for an opportunity to place his order, walks about the camp. He hears the children sobbing and when one of them explains to him that this man was the children’s friend the stranger begins to think that probably the lumberjack is somewhat human. When later in the day he hears of how this “lumberjack” went cheerily whistling to his work each morning, of his courtesy to all woman, of his kindness in taking care of an old man in the camp, and of how he was ever ready to help anyone in need, he understands why the woman and children, and even some of the “loggers”, are sobbing.

We are proud of our lumber industry and we boast of our timberland as one of our greatest natural resources. But when we see the great carloads of lumber do we stop to think of the work it has taken to place this lumber on the market, or do we take time to be interested in the lives of those whose work contributes to the lumber industry.

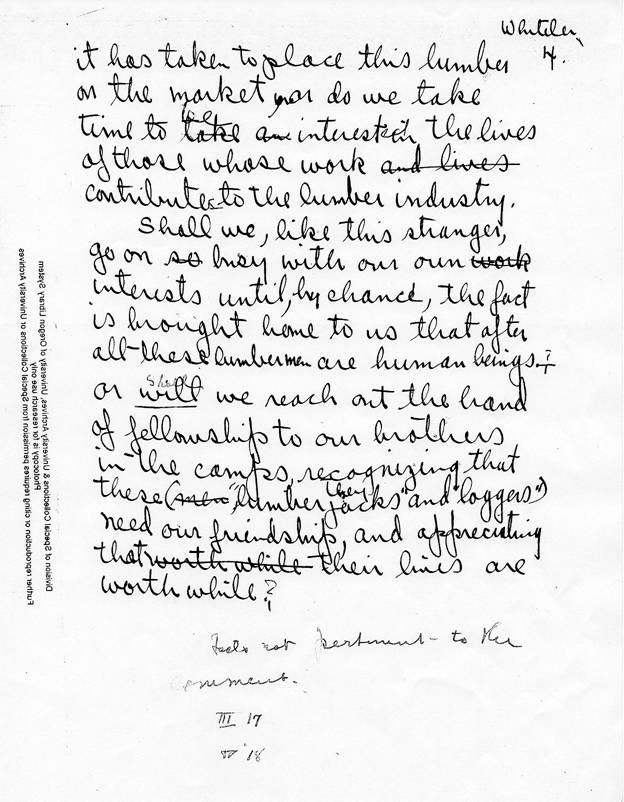

Shall we, like this stranger, go on busy with our own interests until, by chance, the fact is brought home to us that after all these lumbermen are human beings? Or will we reach out the hand of fellowship to our brothers in the camps, recognizing that these lumberjacks and loggers need our friendship, and appreciating that their lives are worthwhile?

————— END —————–

NOTE: at the end of the text Opal’s professor wrote, in barely readable handwriting “Facts not relevant to the comment”.

And these numbers II 17 and IV 18. The class was English Composition and this assignment of 520 words was from Lessons three and four.

Her exact grade is unknown, there is an “S” on the front page, which on other assignment papers is an “S+”. Perhaps it means Satisfactory.

She used unlined paper for this assignment. It’s interesting to see how the letters shape themselves – sometimes tilting downward, sometimes upward.